The Book That’s Been Guiding Me Through the Cosmos for Decades

Has any book played such an outsized role in your life that not only did you read it multiple times, but you also owned several different copies?

Books vanish for various reasons—you might lend one to a friend and never get it back, leave one behind at a former job or ex’s house, or lose one during a move—but you replace the important titles, the meaningful ones, because your bookshelf would be incomplete without them.

Several books fall into this category for me. One is “A Fan’s Notes” by Frederick Exley, the inspiration behind this blog, as I documented last year in my inaugural post. Others include “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by Robert Pirsig and the writing guidebook “The Elements of Style” by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White.

Whenever I realized one of those was no longer in my possession, which happened more than a few times with each, I immediately drove to the bookstore to buy a replacement copy.

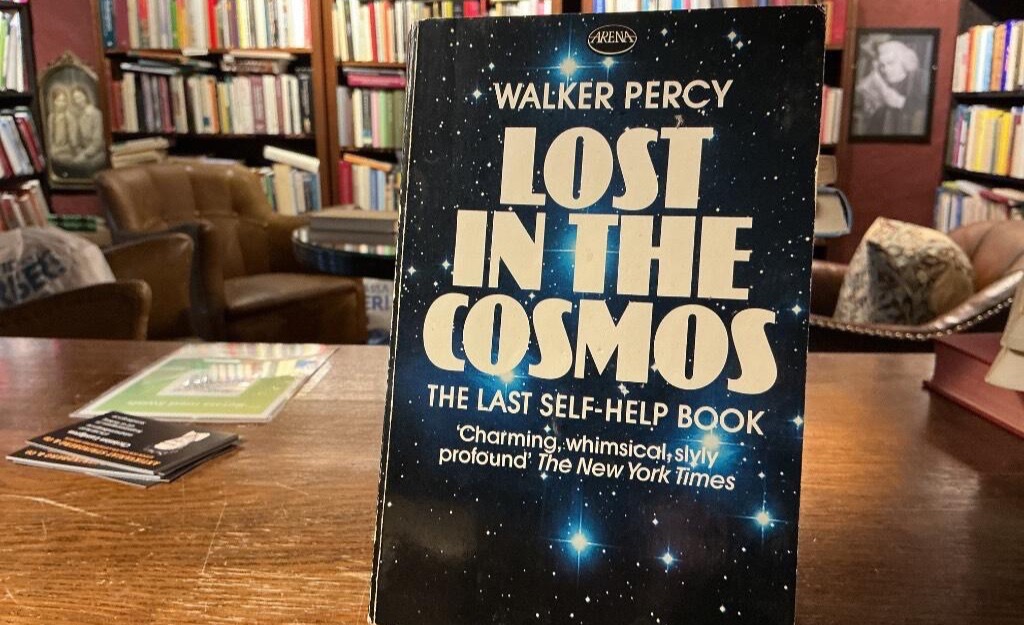

Today’s post focuses on another pivotal book I’ve always made sure to own—Walker Percy’s “Lost in the Cosmos,” the nonfiction classic that transformed my life when I was introduced to it 34 years ago this month and which continues to resonate all these decades later.

I haven’t owned as many copies of “Lost in the Cosmos” as the books mentioned above, but I’m certain I’ll always keep one on hand.

Why? Because it’s an old friend. A comfort read. A go-to when things get confusing and I need to remember where I started, how I got to this point in my life, and where I’d still like to go.

My latest blog for “A Fan’s Notes” will explain. And it begins with a brief story of how this peculiar but powerful book found its way into my orbit.

The universe unfolds as it should

My introduction happened at precisely the right time—when I was a 20-year-old college junior starting to figure out what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be. It was my proverbial “finding yourself” phase, as it is for many that age.

The year was 1991. One October afternoon, when the Rhodes College campus was ablaze with fall colors and the beauty and sadness of the season were at their peak, I was chatting with a friend and fellow English major named Cliff Watson.

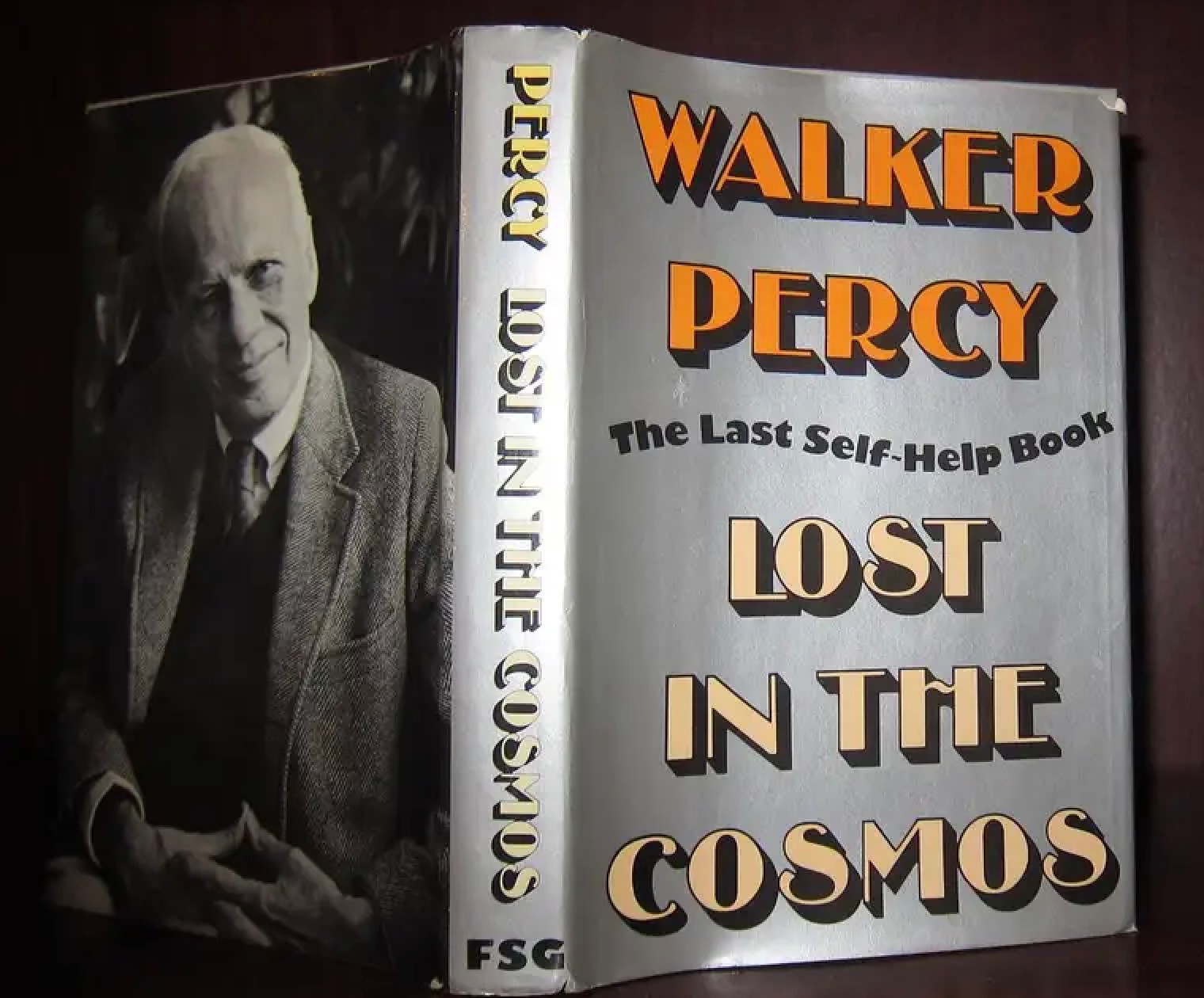

As we caught up, I noticed a book he was holding. It had a gray cover and orange and beige type with the title “Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book.”

When I asked Cliff about it, his eyes lit up. In an instant, I sensed he was about to share something life-changing.

“Lost in the Cosmos,” he exclaimed, was a must-read by the Southern novelist Walker Percy (1916-1990). The author, renowned for his fiction such as the National Book Award-winning novel “The Moviegoer,” managed to satirize the self-help genre while providing a philosophical exploration of humans and our place in the universe.

Cliff flipped to one of several pages he had bookmarked and handed it to me. He knew I’d appreciate the section called “Why Writers Drink.” As an English major who might pursue writing and who definitely enjoyed drinking—maybe a little too much, admittedly—I was intrigued. I needed to investigate further.

The next day, I drove to Bookstar on Poplar Avenue in Memphis—a fantastic former bookstore housed in an old movie theater—bought a copy of “Lost in the Cosmos,” and began reading when I returned to my dorm room.

I don’t remember how long it took me to finish the book—perhaps two or three sittings, maybe a week—but with each page I turned, with each chapter I completed, with each insight Percy offered into the complex existence of the self and why humans are the way we are, my fanaticism for the book and author grew.

Journey through the cosmos

“Lost in the Cosmos” was unlike anything I had read before. Percy had a unique way of looking at the universe and people, and his worldview was evident from the beginning.

On the title page, for example, he listed several alternate subtitles for the book, each one humorous yet thought-provoking:

The Strange Case of the Self, Your Self, the Ghost Which Haunts the Cosmos

-or-

How you can survive in the Cosmos about which you know more and more while knowing less and less about yourself, this despite 10,000 self-help books, 100,000 psychotherapists, and 100 million fundamentalist Christians

-or-

Why it is that of all the billions and billions of strange objects in the Cosmos—novas, quasars, pulsars, black holes—you are beyond doubt the strangest

-or-

Why it is possible to learn more in ten minutes about the Crab Nebula in Taurus, which is 6,000 light-years away, than you presently know about yourself, even though you’ve been stuck with yourself all your life

Percy begins the book with a self-help quiz so readers can determine if they are indeed lost in the cosmos. The questions touch on personality, identity, sexuality, religion, consciousness, and much more, all designed to uncover how well a person understands their self—who they truly are.

Those who don’t feel strange, alienated, or lacking in purpose, those who aren’t filled with despair, dread, or detachment, those who can make it through an ordinary afternoon without wanting to put a bullet through their head, may close the book and move on comfortably with their lives. They aren’t lost in the cosmos.

I wasn’t in that camp, so I kept reading.

The book then delves into many topics, all of which center on the idea that we are lost to ourselves, to each other, and to the world itself. We struggle to find meaning for various reasons. But rather than providing a map to find oneself, Percy wants the reader to figure it out, to deduce why they’re lost, and then create their own map for getting back on track.

Percy’s provocative text posed existential questions, offered commentary on the modern world, challenged the meaning of humans’ existence, and pondered how we wayward voyagers should and could navigate the cosmos—aka, life.

Uniquely structured with “thought experiments,” quizzes, and ridiculously hilarious scenarios throughout, “Lost in the Cosmos” was written to help us on our perilous journey through the cosmos by asking questions rather than providing answers. Percy puts the onus on each person to identify what’s wrong with them and then seek solutions.

It was precisely the nudge I needed to begin the next phase of my journey.

Lost, now found?

“Lost in the Cosmos” is filled with memorable quotes and ideas that could each be the subject of their own blog. The point of this post isn’t to analyze the entire text, nor to expose my own shortcomings, faults, and neuroses, which are plenty, but rather to cull a few highlights and show why I connected with the book so strongly.

For example, in the section “Why Writers Drink,” one of the passages that persuaded me to buy my own copy, Percy describes why writers turn to alcohol at a rate that exceeds most others who pursue the arts.

It’s because writers—unlike painters, for example, who can joyfully mess around with colors on a canvas to spark their creative juices—are resigned to staring at a blank piece of paper and creating art out of literally nothing. Percy writes:

“He (the writer) works alone in a room as bare as a Quaker meeting house with nothing between him and his art but a Scripto pencil, like God’s finger touching Adam. It is harder on the nerves.”

And because writing is so tough on the nerves, Percy argued, the easiest fix is a “chemical assault on the cortex of the brain,” i.e., booze. Such a simple explanation made sense to 20-year-old me. It still makes sense all these years later.

Another passage that resonated and helped propel my life’s journey was his descriptions of how humans view the concept of “home.”

Many of us have a complicated relationship with where we grew up—a theme Percy explored in several books beyond this one—and the below line sums up this predicament better, or at least more simply, than anything else I’ve read.

“Home may be where the heart is, but it’s no place to spend Wednesday afternoon.”

That one hit hard when I first read it. Even though I was attending college in my hometown of Memphis, which I loved and still love from afar, I was already looking at ways to get out. I needed to at that stage in my life.

Over the next year and a half of college, I would eventually figure out my path, one that led me to London and then Alaska, as I outlined in another blog about an equally influential book, How Jon Krakauer’s ‘Into the Wild’ Changed My Life.

I did move back to Memphis later in life—there is a whole other blog about that period in the works—but even then, Percy’s words crept back into my brain when my wife and I chose to head west to Colorado.

That was one of several ways “Lost in the Cosmos” reoriented me in the right direction at the right time.

A cosmic guide

I have returned to Percy’s book often over the years because it’s funny, poignant, and thought-provoking. Whatever page I open it to, I usually find something new that reinforces the book’s importance in my life or, at least, makes me chuckle.

“Lost in the Cosmos” is also relevant in the mid-2020s, maybe more so than when Percy published it in the early 1980s. Take, for example, the below quote. He wrote this more than 40 years ago, yet it still rings true today, perhaps truer than ever:

“You live in a deranged age—more deranged than usual, because despite great scientific and technological advances, man has not the faintest idea of who he is or what he is doing.”

With vacuous hobbies like social media, rampant political chaos, and the scourge of artificial intelligence replacing art, it’s unlikely Percy could’ve imagined an age as deranged as the one we live in now.

I view “Lost in the Cosmos”—along with the other books, bands, poets, and films I’ve written about for “A Fan’s Notes”—as an antidote to the derangement. It’s why I started this blog and why I’ll continue paying tribute to the things I’m a fan of.

As I worked on this latest entry, I flipped through “Lost in the Cosmos” again for the first time in a few years. While recollecting favorite passages, I couldn’t help but smile as I thought back to that random moment in 1991 when I bumped into Cliff and he showed me this life-changing book.

I didn’t see it then, but I now marvel at how the universe led me to “Lost in the Cosmos” when I needed it the most and how the book has continued to guide me ever since.

It made me realize I’ll be a fan of it forever—or at least until my own weird, winding, and wondrous journey through the cosmos has reached the end.

0 Comments Add a Comment?