The Transcendence of James Wright’s Poetry

During my sophomore year at Rhodes College, I took a poetry workshop where we divided our time between writing verse, critiquing classmates’ poems, and analyzing the work of published poets.

I won’t subject readers to the garbage I wrote back then, so this blog is about a 20th-century great unknown to me until that class began on a late August day.

Our curriculum included several heavyweights of contemporary American poetry—Robert Lowell, Adrienne Rich, Louis Simpson, Philip Levine, and others—but one poet stood out. A poet who’s now my latest subject for “A Fan’s Notes.”

That poet was James Wright, a post-war, Pulitzer Prize-winning author who had died a decade earlier in 1980. Known for his plainspoken verse and honest descriptions of desolate Midwestern locales and their working-class denizens, Wright’s work resonated with me immediately. His poems were more powerful, more poignant, than anything else I read that semester and perhaps in my entire college career.

Even though I later pursued a career in journalism rather than poetry or academia, I remain a huge fan and regular reader of Wright. He is one of a few poets whose collections I still pull down from my bookshelves on occasion to remind myself of the impact his verse had in my life—an impact I still feel 30-plus years later.

To honor what he’s meant to me, I figured it was time to dedicate a blog to James Wright, his honest and heartfelt poetry, and the legacy they’ve had on my life.

Poems that will ‘break your fucking heart’

On Day 1 of that poetry class, our professor, Dr. Richard Lyons—an accomplished poet who taught me much about writing—outlined the syllabus and introduced the authors we’d be reading that term.

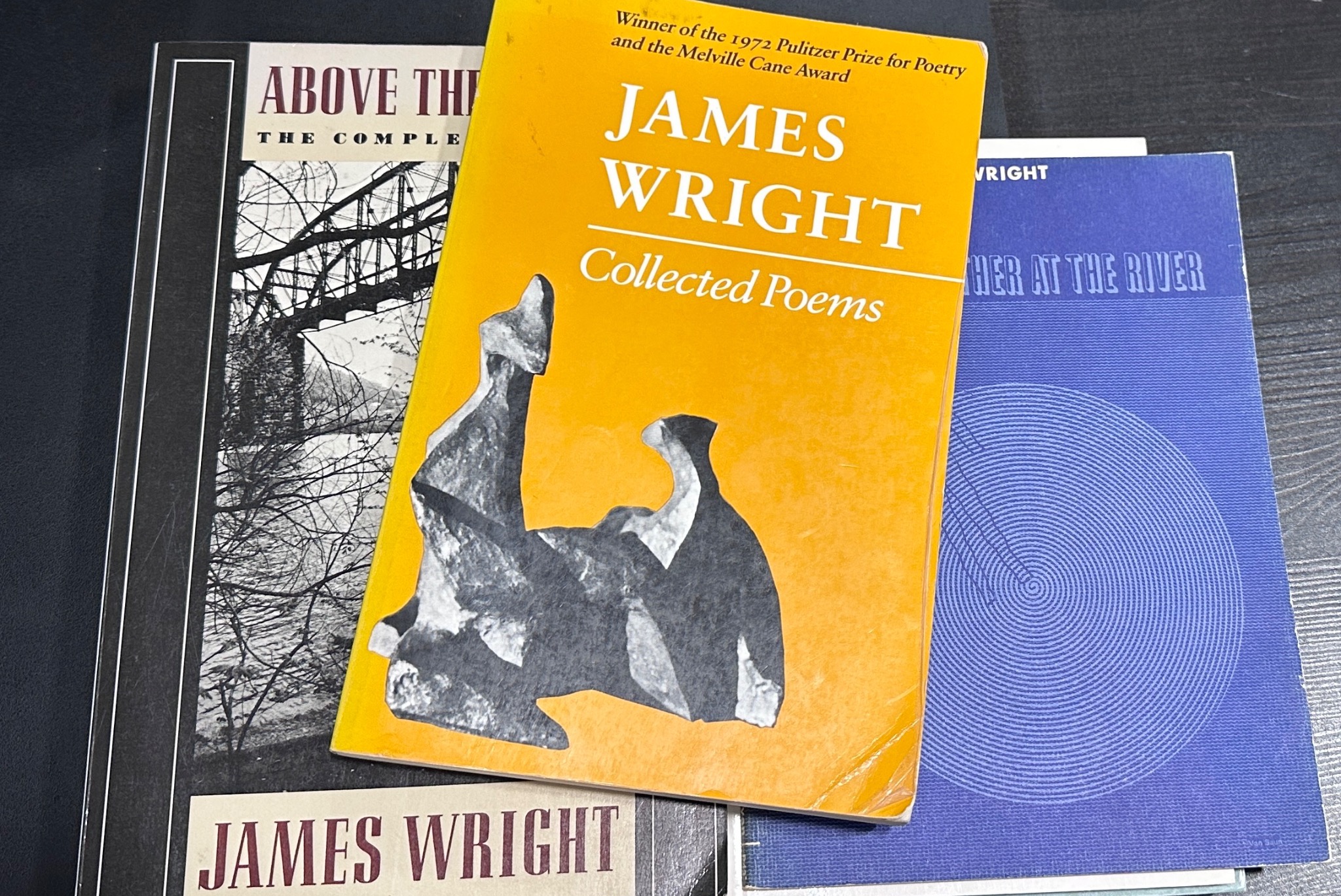

Among the first books he discussed was Wright’s “Collected Poems,” winner of the 1972 Pulitzer Prize and the Melville Cane Award. I still own my original copy from that semester. Its frayed cover, notes in the margins, and smudged pages are testaments to decades of leafing through it for new poems to discover.

I don’t remember everything Dr. Lyons said about Wright that day, but I recall the moment he paused in mid-thought and contemplated Wright’s import before moving on to the next subject. He held the book in his hands, gazed upon its cover, and reflected on the lines within—lines his students would soon be poring over and trying to make sense of.

“There are passages in here,” he said, “that will break your fucking heart.”

Over the next few weeks, I learned it was true. Each time I read a Wright poem—whether in the solitude of my room, the shaded solace of Fisher Memorial Garden, or the library stacks on a lonely weeknight spent writing and studying—I was drawn deeper into Wright’s sad, faraway world that somehow felt familiar. I was also drawn to a career in writing, whatever form that might take.

As our class tackled several of Wright’s poems, analyzing their vivid descriptions of deep sorrow and sympathetic characters, I quickly became a fan.

Wright wrote of love and longing, death and despair, vulnerability and strength, stark landscapes and the remarkably unremarkable people who inhabit them. The breadth and depth of his vision can be seen, and felt, in poems like “At the Executed Murderer’s Grave,” “Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio,” and “A Blessing.”

I latched onto passages like the opening stanza of “The Minneapolis Poem,” Wright’s lament for “legless beggars” and other personae non grata he so often wrote about with unpatronizing empathy:

I wonder how many old men last winter

Hungry and frightened by namelessness prowled

The Mississippi shore

Lashed blind by the wind, dreaming

Of suicide in the river.

As I read descriptions of places I had never before drawn breath—his home turfs of Ohio, West Virginia, and Minnesota—and the plights of people I had never met—America’s forgotten steel workers, prostitutes, and “unnamed poor”—Wright made these places and those people come to life. They blossomed before me.

Two perfect poems

I could dive deep into several of Wright’s poems, including the ones mentioned above, but I’ll share the two works that have stuck with me ever since that early autumn more than three decades ago. Two that transcended all others.

The first is arguably Wright’s most famous poem, the pastoral “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.” It’s brief—only 13 lines and 83 words—but the poem touches on several themes that dominate Wright’s oeuvre: isolation, melancholy, nature, and the inherent struggle and sadness of life.

Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

Down the ravine behind the empty house,

The cowbells follow one another

Into the distances of the afternoon.

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

–James Wright

That final line—a surprising epiphany after describing a peaceful natural scene—has haunted me since I read it. I always felt it foreshadowed something similar for future me. Will I someday lie in a hammock, surrounded by beauty but rueing my wasted life?

Our class was divided on how well the poem worked. Some liked the sudden emotional shift at the end. Some thought it was trite. All of Wright’s work was divisive, and as I think back, I was among his few unabashed fans. While some criticized his simplistic style and language, I celebrated it.

The second poem I’ll share here—another one that has stayed with me for decades and whose two final stanzas I can recite by heart—is “To the Muse,” the final poem from Wright’s book “Shall We Gather at the River.”

It’s a spare and powerful poem that captures Wright’s ability to write plainly and say more—much more—than what appears on the surface. The emotional depth relative to word count is astounding and, yes, transcendent.

To the Muse

It is all right. All they do

Is go in by dividing

One rib from another. I wouldn’t

Lie to you. It hurts

Like nothing I know. All they do

Is burn their way in with a wire.

It forks in and out a little like the tongue

Of that frightened garter snake we caught

At Cloverfield, you and me, Jenny

So long ago.

I would lie to you

If I could.

But the only way I can get you to come up

Out of the suckhole, the south face

Of the Powhatan pit, is to tell you

What you know:

You come up after dark, you poise alone

With me on the shore.

I lead you back to this world.

Three lady doctors in Wheeling open

Their offices at night.

I don’t have to call them, they are always there.

But they only have to put the knife once

Under your breast.

Then they hang their contraption.

And you bear it.

It’s awkward a while. Still it lets you

Walk about on tiptoe if you don’t

Jiggle the needle.

It might stab your heart, you see.

The blade hangs in your lung and the tube

Keeps it draining.

That way they only have to stab you

Once. Oh Jenny.

I wish to God I had made this world, this scurvy

And disastrous place. I

Didn’t, I can’t bear it

Either, I don’t blame you, sleeping down there

Face down in the unbelievable silk of spring,

Muse of the black sand,

Alone.

I don’t blame you, I know

The place where you lie.

I admit everything. But look at me.

How can I live without you?

Come up to me, love,

Out of the river, or I will

Come down to you.

–James Wright

Ostensibly, the poem centers on a man pleading with Jenny, a woman he loves but who is dying. He commands her not to slip away but to return to the world of the living. If she refuses, he will join her in death because he can’t bear to live without her.

At least, that’s how I interpreted it as a 19-year-old. Perhaps there’s some merit to that literal interpretation, really any interpretation, which is the beauty of poetry.

There’s something heartbreaking and universal in that simple explanation—a grieving man at his lover’s deathbed—but the poem is much deeper than that. “To the Muse” centers on the personified relationship of the poet and his inspiration to write, aka the muse. Now the muse has abandoned the artist in his time of need.

Because the muse is dying—the same muse who guides the writer and beckons him to keep pursuing his art because it’s the only thing that matters—he has decided not just to give up writing but to give up life itself. He has no choice but to join his muse in the depths of the “Powhatan pit.”

I imagine those final lines were what Dr. Lyons had in mind when he told us Wright’s work would break your fucking hearts. I know those lines have kept me coming back all these years to see what new heartbreaking passages I might find when I open a book of Wright’s poems.

The legacy of Wright’s words

Thankfully, Wright didn’t give up. He kept writing. He found the strength to keep his muse alive. I’m thankful for that—and for Dr. Lyons introducing me to Wright’s work all those autumns ago.

Wright, however, was more influential than a few passages that made me ponder my existence and wonder if I was wasting my life. Though I didn’t become a poet, his style and his voice have guided me all these years.

It’s hard to think that someone who wound up a sportswriter, business reporter, and casual blogger would dare consider a poet as instrumental in his writing style. But his voice is always present. Wright’s words, tone, emotion, and empathy echo in my brain whenever I put pen to paper—no matter where or what I’m writing.

I may never write anything as poetically perfect as “To the Muse” or “Lying in a Hammock…,” but I take comfort in my ability to revisit those works, transport myself back to the happy, sad, bittersweet autumns of youth, and be reminded why I’m forever a fan of James Wright.

Author’s note: This is another entry in an occasional series on the writing life— something I’ve been a fan of for many years. Look for future blogs on how I broke into the biz, writing as a side hustle, my favorite resource guides, and more.

Post a comment